Clint Eastwood es de esas figuras que pertenecen al cine y que pueden decir que, al menos hasta cierto punto, el cine también les pertenece. Su primer gran huella en la historia del séptimo arte se dió gracias a la fortuita casualidad de que Sergio Leone lo escogiera como el protagonista, el Hombre Sin Nombre, de su Trilogía Dólares ("Por un Puñado de Dólares" del 64, "Por Unos Dólares Más" del 65 y "El Bueno, El Malo y El Feo" del 66). Desde ese momento en que se le retrató como un cazarecompensas frío, estoico y de muy pocas palabras en el Viejo Oeste estadounidense, Eastwood y el personaje se volvieron íconos, el intérprete tan importante como el papel, de la hombría desde el punto de vista del cine de la época y del anti-héroe fallido y gris del spaghetti western.

Luego vendría el Eastwood como gran cabrón de cabrones de los 70s, Harry Callahan, el Sucio. Un policía que juega por sus propias reglas, que a pesar de ya no tener lugar en la fuerza por sus métodos brutales y fuera de la norma. Después sucedieron otras cosas e Eastwood decidió cruzarse al lado oscuro de la cámara y empezar la que, a mi modo de ver, sería la parte de su carrera más influyente y positiva para el cine, Eastwood: director.

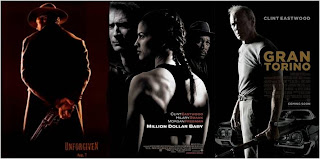

Su primer trabajo como tal fue en "Play Misty for Me" del 71. Pero de las que se centran en la redención, y de las que estaré hablando son "Los Imperdonables" del 92, "Río Místico" del 03, "Golpes del Destino" del 04 y "Gran Torino" del 08 (aunque lanzada en México hasta abril del 09).

"Los Imperdonables" se distingue, en primer lugar, por su relación con el papel icónico de Eastwood como El Hombre Sin Nombre. Un anti-western de primera, donde la violencia se destaca como la única solución, no porque sea la mejor, sino porque no se conoce otra. A la misma en ningún momento se le glorifica o se le pinta con aire de heroismo, de hecho, el personaje de Eastwood aparece ya como quizá el mismo Hombre Sin Nombre, bastante envejecido y francamente hastiado de tanta violencia. En medio de este ambiente, se encuentra la redención, aunque sea solo la personal.

Eastwood está ausente de "Río Místico", pero sus personajes son también representativos de ese ideal de su filmografía: el de los personajes con errores a cuestas, intentando hallar el perdón por los mismos en cualquier lugar posible, decepcionados con el hecho de no poder encontrarlo en donde más se esperaría (la fé, la familia, la amistad).

Regresa para "Golpes del Destino" donde su nuevo personaje icónico haría su debut. ¿El nombre del personaje? "Viejo cascarrabias y terco que aprende una lección gracias a un protegido joven que le recuerda a él mismo y que usa para suplir las relaciones que nunca tuvo con sus hijos".

Y creías que "El Hombre Sin Nombre" era demasiado largo.

En "Gran Torino", Eastwood es el personaje antes mencionado pero en vez de box hay muscle cars e insultos raciales.

Ahora, claro, me parece que hay que señalar que el tema central de todas estas películas y, por lo tanto, uno de los temas de la filmografía de Eastwood, es la redención. Las cuatro películas se destacan por tener como protagonistas a personajes con pasados algo brumosos, marcados por errores que sólo quieren dejar atrás. En todas se ven obligados a enfrentar el error en sus vidas actuales gracias a algún factor. En "Golpes del Destino" es la boxeadora terca que quiere ser entrenada por Eastwood sin importar qué. En "Gran Torino", el francamente inútil vecino asiático.

Sus hijos en "Gran Torino" son egoístas y convenencieros, mientras que la de "Golpes de Destino" está sencillamente ausente. En ambas (y en "Río Místico" también si no mal recuerdo) también aparece otro personaje medio común de la filmografía de Eastwood: el padre católico irlandés.

Probablemente relacionado con personajes de la propia vida del cineasta, este personaje siempre se muestra en una posición opuesta a la del personaje de Eastwood, que gusta de burlarse del mismo. Los padres siempre buscan a Eastwood, para hacer que hable con ellos o para afirmarle su fé en declive. Aunque, al final de ambas películas, se implica que, al menos hasta cierto punto, ambos padres tenían la razón, pero el personaje de Eastwood simple y sencillamente hace lo que hace porque tiene que.

En ese sentido, la redención para Eastwood solo se encuentra en dos lugares. El primero es el sacrificio. En "Los Imperdonables" y "Gran Torino", este es total (y magníficamente opuesto), mientras que en "Golpes del Destino", es principalmente de la estabilidad psicológica y emocional .

El segundo es el perdón. Un perdón muy cristiano, y que se muestra como la solución ideal, y por lo tanto, la que no va a pasar.

____________________________________

Clint Eastwood is one of those figures that belong to cinema and can, to a certain extent, say that cinema belongs to them as well. His first big legacy in the history of the seventh art came from the sheer coincidence of being chosen by Sergio Leone to star as the protagonist, the Man With No Name of his Dollars Trilogy ("For a Fistful of Dollars" '64, "For a Few Dollars More" '65 and "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly" '66). From that moment, when he came to portray a cold, stoic, silent U.S. Old West gunslinger, Eastwood and his character acquired iconic status, the actor as important as the role itself, as a symbol of its time's views on manhood and as the typical failed, grey anti-hero of the spaghetti western.

Afterwards, we'd get Eastwood as the true, utter asskicker of the 70s, Dirty Harry Callahan. As a loose-cannon cop, playing by his own rules, and still in the force's payroll due the fact that, dammit, he's still the only one that gets things done. A lot of other things happened later and Eastwood found himself on the dark side of the camera and began what, to me at least, would be his most influent and important career in film, Eastwood: director.

His first job as such came with "Play Misty for Me" from 1971. But those focusing on redemption and, as such, the ones to be discussed here, will be 92's "Unforgiven", 03's "Mystic River", 04's "Million-Dollar Baby" and 08's (released in Mexico in April '09, though) "Gran Torino".

"Unforgiven" is distinguished, first of all, due to its relation with Eastwood's iconic role as the Man With No Name. A true-and-through anti-western, where violence is highlighted as the only solution to all of life's problems, not because it's the best, but because it's the only one known to all. Violence itself is never glorified or seen with airs of heroism, in fact, Eastwood's character is perhaps the older version of the Man With No Name himself, now completely sick of a life of violence. In the middle of this, redemption, at least on a personal level, can be found.

While Eastwood is nowhere to be found on "Mystic River", this film showcases his ideals as well on its characters: flawed and burdened with the mistakes of their past, looking for forgiveness, but not finding it even where it's supposed to be (with your family, faith, friendships).

He's back in "Million Dollar Baby", where his new iconic character debuted. The character? "Grumpy, stubborn old man that learns a lesson thanks to a young protegé that reminds him of himself and that he uses to make up for the relationships he doesn't have with his offspring".

And you thought "The Man With No Name" was too long.

In "Gran Torino", Eastwood revives the character, but instead of boxing, we have muscle cars and racial insults.

Of course, now's the time to point the central theme in all these films, and thus one of the main ones in all of Eastwood's filmography: redemption. All fours movies are distinguished by the presence of characters with blurry pasts, with mistakes they only wish to leave behind. Yet, in all, they're forced to face their past mistakes thanks to some external factor. In "Million Dollar Baby", it's the boxer, wanting to be trained by Eastwood no matter what. In "Gran Torino", it's the frankly useless Asian neighbor.

Eastwood's children in "Gran Torino" are selfish and only look after their own interests, while his daughter in "Million Dollar Baby" shines for her absence. Both (and also "Mystic River" if I'm not mistaken) also feature the presence of another Eastwood staple character: the Irish Catholic padre.

Probably related to characters in the filmmaker's life, this character will always show as a contrast to Eastwood's, who'll always mock him. The padre actively tries to get closer to Eastwood, whether it's to get him to restablish his faith, or just for talking. Although, by the end of both movies, the padre is shown to be at least somewhat right, but Eastwood's character does what he does simply because he has to.

In that sense, redemption for Eastwood can only be found in two places. The first is sacrifice, from the total (yet magnifically opposite) ones in "Gran Torino" and "Unforgiven" to the emotional and psychological one of "Million Dollar Baby".

The second is forgiveness. A good, Christian forgiveness is always shown as the only right way and, as such, the impossible way.